(Written about a week and half ago.)

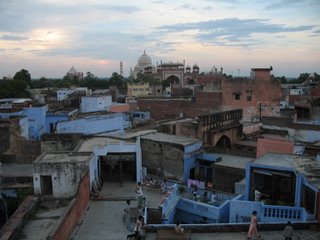

Alchi, Ladakh

Link to current photos.

Tomorrow we leave for Kashmir. As of today, we've spent three weeks in Ladakh, longer than any single place since we pulled out of our driveway back in December. In the time we've been here , the potato fields that were green when we arrived, have started to flower en masse. This seasonal tick of nature's second hand was the kind of chronology I sought as I sat at my desk at work. In San Francisco, seasons are so subtle that, if you spend most of your time indoors as I did, you can look out a window and guess blindly where you're at on the calendar. This can be shockingly disorienting for anyone with a sense of his mortality. I play a game now where I try to think back over the preceding months and remember where we were on the nights of the full moon. Good memories are made like this.

Ladakh, sitting on the militarily sensitive border with Pakistan, has been closed to all but Ladakhis and the Indian army prior to 1974, the year it was opened to tourism. Politics played as big a part as economics in the change of policy change. Some observers speculate that Ladakh was opened to tourists primarily as a measure to cement the validity of India's claim on a land that, culturally, is very different from the nation that exists in the huge land south of the Himalayas. Ladakh is one of those red-headed stepchildren in the hastily cobbled geography left by the retreating colonialists. For this reason and its mountainous isolation, Ladakh was unique in that it remained relatively untouched by Western industrialization or materialism.

This uniqueness raised some questions which fed into a continuation of a discussion with Shawn from the prior post. He asked if it is ethical to "travel in an area known to be teetering on the edge of famine?" I don't think his description was meant to apply to Ladakh (which currently suffers no shortage of food) but to other places he referred to in the developing world. It's of no matter, though. After I reflected on his question it became clear to me that a person of the US, if he or she is able, has an obligation to travel to countries in the developing world. I think each and every person should get the hell out and see what life is like in places where people live with their hands never far from their proverbial mouths. A person can learn some things about compassion, humility and gratitude that can't help but make them better.

The example of Ladakh is useful because here, you can still see something that is simply too complex to grasp in the Western world: a complete model of the natural resource systems that are needed for humans to live. I say

still because even Ladakh is changing quickly and this insight will get more difficult to appreciate if development continues as it currently is.

Before 1974 and for centuries prior, Ladakh was a fully self-sufficient area. People sent trading caravans over the high mountain passes to other areas for a few things like salt but, for the large extent of what they needed to live, Ladakhis produced it themselves. They made their own clothes with wool from their sheep and natural dyes from plants and minerals. They saved some seeds from each year's harvest for future planting. They made houses out of poplar logs, adobe bricks and mud stucco. They cooked over dung fires. They fertilized their fields with human feces collected in composting toilets that was mixed with ash and wood shavings. It was a society with, literally, no waste.

With the introduction of the military and later, tourists; packaged goods, electricity, diesel jeeps and trucks, manufactured clothes, commercially grown food and other products from an industrializing India; the closed-loop system that sustained the Ladakhis throughout their history started to unravel. The results range from the obvious to those that are indiscernible to outsiders but all, to some degree, are destructive. If you walk anywhere in Ladakh, you will see the discarded plastic packaging of snack foods candy, laundry soap and on, and on. The Ladakhis never had a need for sanitation trucks and landfills and the introduction of these goods comes with no direction as to the proper disposal of their wrappings after the consumption of the contents. Ladakh, a network of fragile, high-mountain, desert ecosystems nutured with centuries of irrigation, terracing and careful planting, is becoming a plastic-filled mess.

Roadside Waste Disposal

Roadside Waste DisposalMy point is not to blame the Ladakhis for being litterbugs. I could also talk about the use of pesticides that are banned in the Western world or genetically engineered seeds (those are here as well). I could talk about how large trucks carry subsidized (and non-native) food into Ladakh from the southern plains rendering local agriculture economically unsustainable and the valley air smoggy.

The point is, that for most of their history, Ladakhis could see the end result of virtually all of their decisions and actions. They knew exactly where their food came from. They knew if they needed to build another house where all of the materials could be obtained and who would help them build it. For over a thousand years they lived in a large collection of green, reasonably prosperous valleys. Now, after a few decades that is rapidly changing.

The young people have little interest in working the farmlands. They are drawn to the 'glamour' and wages of the tourist trade. From what I could see, a good portion of that precious and very limited farmland is being given over to the building of an astonishing number of new guesthouses for tourists. I wonder, if the need should ever arise, they'll pull down the houses to grow food. I've seen the same changes around any number of cities in the Midwest or the central valley of California. Useful farmland, for all practical purposes, permanently entombed under huge subdivisions courtesy of shortsighted planning commissions and Pulte or KB Homes.

A place like Ladakh is a microcosm of our natural world and what makes it a destination worth visiting is that, here, you can see the results of what happens when a person makes a decision about consuming something. If you use certain things, there will be costs and waste. If you want to eat, you wait for the seasons to work their magic on the fields and, if you're lucky, you grow what you need. Most importantly, you can see and have an innate understanding that those resources that sustain life are not infinite.

At home, in the States, you don't see the costs. The plastic we use goes into a landfill but it doesn't go away. You use that same plastic or pump some gas into your car but, unless you're getting uncensored news from inside Iraq, you don't see the human suffering caused by securing the petroleum needed to make the plastic or gas. While that nice farmland outside Ann Arbor is being paved for another subdivision of McMansions, in places like Nevada or Idaho, you have massive industrial farms that exist because land there is cheap and agribusiness uses subsidized water to farm in earth that is nothing more than a sponge for natural gas derived fertilizers and oil derived pesticides.

But we've always been able to look away from those "costs" is we dont' like what we see. The garbage goes into the ground. If you don't like living in Saginaw or Stockton, you move. Costco and Sam's Club don't run out of lettuce or Tide or strawberries so why worry about how they get to the store. Detroit keeps making huge gas hogs so they must know something about the oil supplies, right? Politicians, news commentators and even some 'scientists' tell us we have nothing to worry about with respect to the environment or oil supplies. What to believe....?

I keep hearing that technology will keep coming up with solutions to resource issues. Well, here I am in Ladakh, an area in the nascent stage of being "developed" in the Western style and the resultant problems of material consumption look just as bad if not worse than every other place that had to go through "development". It's two thousand and freaking six and we still can't even deal with potato chip bags and clean water! If ever there were a time to bring some of that technology to bear, it is now and here. Yet, apart from a few, small, underfunded, non-governmental organizations working to stem the tide of consumption and waste, it's business as usual in Ladakh...which, I can assure you, will lose what makes it unique if this continues. And, if a small place like Ladakh with a long history of sustainable self-management can't continue to live within its resources, how in the hell will the rest of the world?

Helena Norberg-Hodge, a linguist who has lived and studied among the Ladakhis since the area opened, says that "In the West, our arms have grown so long that we don't know what our hands are doing." Visiting a place like Ladakh or Sudan or Guatemala or most any other "undeveloped" country helps to remind and illustrate for us that, for every comfort, there are costs. The question is, how long can those costs be sustained?

"...it has been calculated that if all the worldÂ’s people had an American standard of living, two more planets the size of Earth would be needed to support them." That's tough to get your head around but, if you spend some time in a place like Ladakh, you can extend the logic out from what you see....and maybe it makes sense.

None of the above is new info to a lot of people. I am one more person sounding the "sky is falling" alarm. I would love to go to my grave a "Chicken Little". I will not bet that direction, though. Perhaps one more voice bouncing around the echo chamber of human consciousness will help more people to see, despite what Dick Cheney or Bill O'Reilly say, we are headed for trouble and we'd better look for ways to change. Places like Ladakh have shown us some of those ways and if you have any interest, you can come see for yourself.